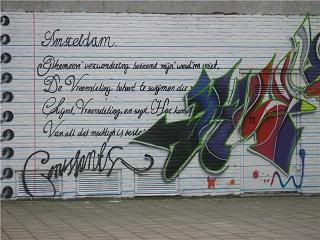

Amsteldam

"Ghemeen’ verwondering betaemt mijn’ wond’ren niet,

De Vreemdeling behoort te swijmen die mij siet.

Swijmt, Vreemdeling, en segt, Hoe komen all’ de machten

Van all dat machtigh is besloten in uw’ grachten?

Hoe komt ghij, gulde Veen, aen ’s hemels overdaedt?

Packhuys van Oost en West, heel Water en heel Straet,

Tweemael-Venetien, waer’s ’tende van uw’ wallen?

Segt meer, segt, Vreemdeling. Segt liever niet met allen:

Roemt Roomen, prijst Parijs, kraeyt Cairos heerlickheit;

Die schricklixt van mij swijgt heeft aller best geseyt."

Bemkah gave me this photo of the first four lines of the poem painted at the entrance of a canal, which is a rather fitting place for it.

And now the English translation:

Amsterdam

Usually not astonished as by a miracle,

The stranger must be dizzy when he sees me.

Become dizzy, Stranger, and say, 'Why is all the power,

All that power closed in your canals?

How did you get, golden Veen, some of Heaven's splendour?

Warehouses from East to West, all along the canals and the streets,

Twice Venice's size, where is the end of your walls?

Say more, say, Stranger. But do not say with all:

Honour Rome, Praise Paris, shout Cairo's glory;

The worst of my silence has said it the best of all.

Petra, denk je dat dit een goede vertaling is? Ik denk 't wel!