There are many problems plaguing our university libraries, which many people do not konw about. One of them, as Robert Darnton explains in this New York Review of Books article, is the astronomical subscription costs to academic journals, which cost thousands of dollars.

Darnton ends his article with the hope that academic sorts of information from the US will one day be freely available to all, just as national libraries around the world are putting their collections online for all to access - these include the national libraries of the Netherlands, France, Norway, Finland, Japan and Australia. Darnton's call to change the commercialised control of information to an open and free system is heady and wonderful, and makes me hope along with him that we can 'Open the way to a general transformation of the landscape in what we now call the information society.' He states that we need a new ecology of information, 'One based on the public good instead of private gain.' And considering the billions of dollars in profits gained by publishers of periodicals, who often don't even bother to pay the academics who put in much hard reviewing and editing work, the public good has long enough suffered for the interest of shareholders!

Sunday, December 12, 2010

Thursday, November 18, 2010

best bookish buying...

If you're looking for a book that has proved impossible to find in bookstores, try Better World Books for book purchases that help fun global literacy! I personally love this website, since you can get second hand books, pay just twenty cents for carbon offsets for the shipping, and at the moment not even have to think about the exchange rate difference! I've yet to see if the free chocolate is sent to Australia as well as in the US...

Oh books, books, books, in case you haven't noticed, I really love books!

Oh books, books, books, in case you haven't noticed, I really love books!

Sunday, July 11, 2010

Literary Melbourne

A delightful new addition to the realm of reading is Literary Melbourne: A Celebration of Writing and Ideas, edited by Stephen Grimwade. A great read, and, if you're one of those strange people who is stuck for reading material, this volume will certainly provide you with enough books to form a lengthy reading list. As the title suggests, the book follows Melbourne's literary history from the art and stories of the area's first habitants to the novels and poetry of the present day. It is particularly fascinating to see, through two centuries of white Australian writing, the change from a dependence on England for ideas and values to a focus on writing about life in Victoria in the early twentieth century, writing that reflected local mores, and then to the plethora of mulitcultural writings that have come out of Melbourne, and also the many children's writers that have lived and written in Victoria, as well as poetry, crime fiction and plays.

The difference between modern fiction and the works produced during the colonial era is made clear by Grimwade when he introduces the segment on modern fiction. He writes, '"Truth", in both fiction and history, became contentious territory as writers sought to represent both themselves and the inner lives of characters. The artistic culture was maturing and our writers and artists could be more provocative. Literature wasn't seen to be the place for simplified "nation building", especially in an era when the nation state was becoming a blurred concept. Novelists were less self-conscious about their nationality and, as the literatures of the world's cultures mixed with our own, Australian authors began to be read more widely across the globe.'

The chapter on migrant writing, in particular, has excellent, moving extracts from novels that reflect the hopes, regrets and realisations of those who have come to Australia from other countries. From Arnold Zable's Cafe Scheherazade we read, 'So join us, dear reader. Don't be shy. Here, have a slice of Black Forest cake. On the house. And a glass of red. Savour it. Feel the glow spreading over your cheeks. Allow the taste to linger in your mouth. It is a pleasant feeling, no? Are you comfortable? Sit back. Settle into your chair; and listen to bobbe mayses, grandma tales.' These 'grandma tales' recount the horror that awaited the Polish returning from armies and labour camps to what had once been homes, but were now, 'piles of rubble, twisted girders, the razed hamlets, the wastelands of defeat. Nothing could have readied them for the scorched earth, the ruined cities, the desecrated temples and shattered homes. This is when their stories began to be suppressed ... by an urgent need to forget, to bury the past and to rebuild their aborted lives.'

The difference between modern fiction and the works produced during the colonial era is made clear by Grimwade when he introduces the segment on modern fiction. He writes, '"Truth", in both fiction and history, became contentious territory as writers sought to represent both themselves and the inner lives of characters. The artistic culture was maturing and our writers and artists could be more provocative. Literature wasn't seen to be the place for simplified "nation building", especially in an era when the nation state was becoming a blurred concept. Novelists were less self-conscious about their nationality and, as the literatures of the world's cultures mixed with our own, Australian authors began to be read more widely across the globe.'

The chapter on migrant writing, in particular, has excellent, moving extracts from novels that reflect the hopes, regrets and realisations of those who have come to Australia from other countries. From Arnold Zable's Cafe Scheherazade we read, 'So join us, dear reader. Don't be shy. Here, have a slice of Black Forest cake. On the house. And a glass of red. Savour it. Feel the glow spreading over your cheeks. Allow the taste to linger in your mouth. It is a pleasant feeling, no? Are you comfortable? Sit back. Settle into your chair; and listen to bobbe mayses, grandma tales.' These 'grandma tales' recount the horror that awaited the Polish returning from armies and labour camps to what had once been homes, but were now, 'piles of rubble, twisted girders, the razed hamlets, the wastelands of defeat. Nothing could have readied them for the scorched earth, the ruined cities, the desecrated temples and shattered homes. This is when their stories began to be suppressed ... by an urgent need to forget, to bury the past and to rebuild their aborted lives.'

Friday, June 25, 2010

Read of late, and yet to read...

I have been reading Alice Walker, the black womanist writer and activist, who is by all accounts a marvellous woman, and I am honoured to be reading her thoughts and experiences - her words as a woman and a writer are very inspiring to me, and I feel that I want to write when I have read just a few pages of her work. Her wise words help one to be more aware of needing to have compassion and empathy for all humans, and the Earth itself, and to live with integrity, strength, and yet joy - a deep joy that carries us through the difficult and sad parts of life, as well as the better times.

Yet to read:

Journals and Papers: A Selection, Kierkegaard, published by Penguin. I have been wanting to read Kierkegaard ever since my sister Petra started reading his work for honours. I look forward to some stimulating, and, I'm sure, often challenging reading.

Revelations of Divine Love by Julian of Norwich. Technically, I have already started reading this, but only last night, and I am only a few pages in, so I do not want to rush into reflecting on this amazing work.

Orlando by Virginia Woolf, simply because her work is astounding in its simplicity and depth, even as she seems to use too many surface elements, as she seems to in The Voyage Out, which I am currently reading. My deep attraction to her work must come from something in there that touches my heart - I will write about it when it becomes apparent to me. These things cannot be rushed. [EDIT: I realised as I went to bed last night, that 'surface elements' was not what I meant to say, because it seems like 'superficial'; please think of 'signifiers' instead, of leitmotifs and cleverly wrapped truths.]

Her Blue Body Everything We Know, a collection of all of Alice Walker's published poetry from 1965-1990. I think I can only hope to be half as phenomenal as Walker, no matter how long I may live or what I may do. There is such strength and tenacity, and lashings of conviction, in the writing of black woman activists, it is in the work of Maya Angelou as well, a decisive step in the direction of true understanding between all peoples, and none of this imperialistic, patriarchal rubbish, of which the world has had too much, and stifles too many of those it purports to uplift.

Lastly, despite what some say about Labor's policies, and let us remember the Liberals' policies are not any better, and despite what some say that she should have waited until the election to run for PM, I was delighted and proud to see on television yesterday afternoon the swearing-in of Australia's first woman Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, by Australia's first woman Governor-General, Quentin Bryce.

This was an important and historical moment for our country. Tony Abbott really should have credited this at the start of his speech instead of immediately leaping into an attack on Labor's policies - we all know his opinion about those already - and now it seems he does not care about the need for our country to move towards equality of the sexes (one of my colleagues at work described him as misogynistic). I now look forward to the election more than I did a week ago, and I hope to see more equality between the sexes in this country, because it is still an issue, and still a struggle. Indeed, let us also not forget the need to work towards equality for Indigenous Australians and any and all immigrants and people of various religions, and sexual persuasions. Real acceptance and open mindedness seem to be missing in this country.

Yet to read:

Journals and Papers: A Selection, Kierkegaard, published by Penguin. I have been wanting to read Kierkegaard ever since my sister Petra started reading his work for honours. I look forward to some stimulating, and, I'm sure, often challenging reading.

Revelations of Divine Love by Julian of Norwich. Technically, I have already started reading this, but only last night, and I am only a few pages in, so I do not want to rush into reflecting on this amazing work.

Orlando by Virginia Woolf, simply because her work is astounding in its simplicity and depth, even as she seems to use too many surface elements, as she seems to in The Voyage Out, which I am currently reading. My deep attraction to her work must come from something in there that touches my heart - I will write about it when it becomes apparent to me. These things cannot be rushed. [EDIT: I realised as I went to bed last night, that 'surface elements' was not what I meant to say, because it seems like 'superficial'; please think of 'signifiers' instead, of leitmotifs and cleverly wrapped truths.]

Her Blue Body Everything We Know, a collection of all of Alice Walker's published poetry from 1965-1990. I think I can only hope to be half as phenomenal as Walker, no matter how long I may live or what I may do. There is such strength and tenacity, and lashings of conviction, in the writing of black woman activists, it is in the work of Maya Angelou as well, a decisive step in the direction of true understanding between all peoples, and none of this imperialistic, patriarchal rubbish, of which the world has had too much, and stifles too many of those it purports to uplift.

Lastly, despite what some say about Labor's policies, and let us remember the Liberals' policies are not any better, and despite what some say that she should have waited until the election to run for PM, I was delighted and proud to see on television yesterday afternoon the swearing-in of Australia's first woman Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, by Australia's first woman Governor-General, Quentin Bryce.

This was an important and historical moment for our country. Tony Abbott really should have credited this at the start of his speech instead of immediately leaping into an attack on Labor's policies - we all know his opinion about those already - and now it seems he does not care about the need for our country to move towards equality of the sexes (one of my colleagues at work described him as misogynistic). I now look forward to the election more than I did a week ago, and I hope to see more equality between the sexes in this country, because it is still an issue, and still a struggle. Indeed, let us also not forget the need to work towards equality for Indigenous Australians and any and all immigrants and people of various religions, and sexual persuasions. Real acceptance and open mindedness seem to be missing in this country.

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

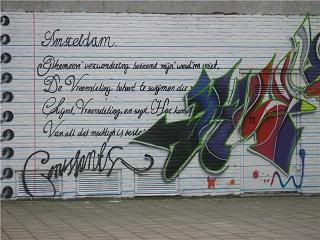

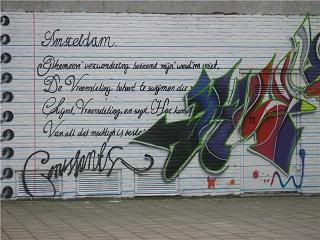

Amsteldam van Constantijn Huygens

This post includes an English translation. When Bemkah first showed me a few lines of this poem, I tried to find an English translation online, but I could not. So my Oma helped me translate the poem, and I think we've gotten the gist of it quite well, though it doesn't sound nearly as marvellous in English as it does in its original Seventeenth century Dutch.

Amsteldam

"Ghemeen’ verwondering betaemt mijn’ wond’ren niet,

De Vreemdeling behoort te swijmen die mij siet.

Swijmt, Vreemdeling, en segt, Hoe komen all’ de machten

Van all dat machtigh is besloten in uw’ grachten?

Hoe komt ghij, gulde Veen, aen ’s hemels overdaedt?

Packhuys van Oost en West, heel Water en heel Straet,

Tweemael-Venetien, waer’s ’tende van uw’ wallen?

Segt meer, segt, Vreemdeling. Segt liever niet met allen:

Roemt Roomen, prijst Parijs, kraeyt Cairos heerlickheit;

Die schricklixt van mij swijgt heeft aller best geseyt."

Bemkah gave me this photo of the first four lines of the poem painted at the entrance of a canal, which is a rather fitting place for it.

And now the English translation:

Amsterdam

Usually not astonished as by a miracle,

The stranger must be dizzy when he sees me.

Become dizzy, Stranger, and say, 'Why is all the power,

All that power closed in your canals?

How did you get, golden Veen, some of Heaven's splendour?

Warehouses from East to West, all along the canals and the streets,

Twice Venice's size, where is the end of your walls?

Say more, say, Stranger. But do not say with all:

Honour Rome, Praise Paris, shout Cairo's glory;

The worst of my silence has said it the best of all.

Petra, denk je dat dit een goede vertaling is? Ik denk 't wel!

Amsteldam

"Ghemeen’ verwondering betaemt mijn’ wond’ren niet,

De Vreemdeling behoort te swijmen die mij siet.

Swijmt, Vreemdeling, en segt, Hoe komen all’ de machten

Van all dat machtigh is besloten in uw’ grachten?

Hoe komt ghij, gulde Veen, aen ’s hemels overdaedt?

Packhuys van Oost en West, heel Water en heel Straet,

Tweemael-Venetien, waer’s ’tende van uw’ wallen?

Segt meer, segt, Vreemdeling. Segt liever niet met allen:

Roemt Roomen, prijst Parijs, kraeyt Cairos heerlickheit;

Die schricklixt van mij swijgt heeft aller best geseyt."

Bemkah gave me this photo of the first four lines of the poem painted at the entrance of a canal, which is a rather fitting place for it.

And now the English translation:

Amsterdam

Usually not astonished as by a miracle,

The stranger must be dizzy when he sees me.

Become dizzy, Stranger, and say, 'Why is all the power,

All that power closed in your canals?

How did you get, golden Veen, some of Heaven's splendour?

Warehouses from East to West, all along the canals and the streets,

Twice Venice's size, where is the end of your walls?

Say more, say, Stranger. But do not say with all:

Honour Rome, Praise Paris, shout Cairo's glory;

The worst of my silence has said it the best of all.

Petra, denk je dat dit een goede vertaling is? Ik denk 't wel!

Friday, March 5, 2010

Surrealism, alienation and hope in Murakami

Welcome to the works of Haruki Murakami, one who writes within what appears to be an ordinary world - until you discover that there are surreal facts of life that would not occur in your own city, not even in the real Tokyo. 12 of his books have been translated into English.

In Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World there is a scientist who discovered that the consciousness is a physical device and can be altered and used to 'shuffle' sensitive data. Unfortunately, for one man whose conscious was involved, he ends up stuck in one particular version of his consciousness - from the outside, he appears to be asleep, but on the inside, the time in his mind is eternally subdividing as he faces a half-life separated from Shadow (his conscious, or soul, which has all of his memories and deep emotions).

In A Wild Sheep Chase a very secretive agency is trying to find one particular sheep in northern Japan. This a very ambitious and ruthless sheep that once inhabited the now-dying man who had become the ultimate controller of Japan, invisibly controlling all government and private sectors.

Compared with these, After Dark does not seem quite so bizarre at first. It is very late at night, Mari Asai is reading in all-night cafe and some trombone player she had met once at a pool comes and starts talking to her. Quite normal. But in the next chapter we find out that Mari's sister Eri has been asleep for 2 months, only waking every now and then to eat or go to the toilet, and she only does that when the rest of the family is asleep or absent from the house. We are an invisible minute camera that can float in the air in Eri's room, and soon see that she has somehow ended up inside a room on the television in her bedroom, and we realise there is no way for her to get out of that room in the television. There is also a Chinese prostitute who got her period at a delicate moment, and is then assaulted by her client. When the gang that had forced the girl into prostitution learns about this, they feel honour bound to defend her, and begin a hunt for the attacker that will not end until the time, some day, some where, he feels a tap on the shoulder. The gang warns him, 'You'll never get away.'

Amongst all this action are some poignant, disturbing tropes. Mirrors that hold the reflections of a person after the person has left the room. A man with a skin-tight mask that betrays nothing of his features or expressions, and yet we can sense where he is staring. People who can keep such a straight face, and such intense eye contact, that it is impossible to know what they are thinking and only feel intimidated. Television screens, some of which act as mirrors, some providing background noise for characters as they go about their daily routine, one of which turns on all by itself and somehow sucks a person into it. These reflections and masks serve a purpose. They show how disconnected society is now, how impersonal, and somewhat unreadable. They show indifference, in people not caring enough to visibly show any feeling on their faces. There is also a hint of the ever-watchful Big Brother in this, that is to say, beneath any of these masks, reflections, diversions, there could be someone watching you, your movements, even hunting you down.

Yet there's a suprising amount of care in the story as well. Humanity's redeeming quality of helping each other when it is needed, and the forming of deep, intense connections between people. Kaoru lets Mari sleep in an unoccupied room in the love hotel, Takahashi and Mari tell each other about fears and memories they had never told anyone else, and finally, after years of feeling distant and separate from her older sister, though they have both lived at home all the time, Mari discovers that she is very closely bonded to her sister and would not want to be without her.

For all of this detail, and the interweaving of several different narratives, this is one of Murakami's shortest works, at only 200 pages. It is a wonderful introduction to his style, and well worth reading.

In Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World there is a scientist who discovered that the consciousness is a physical device and can be altered and used to 'shuffle' sensitive data. Unfortunately, for one man whose conscious was involved, he ends up stuck in one particular version of his consciousness - from the outside, he appears to be asleep, but on the inside, the time in his mind is eternally subdividing as he faces a half-life separated from Shadow (his conscious, or soul, which has all of his memories and deep emotions).

In A Wild Sheep Chase a very secretive agency is trying to find one particular sheep in northern Japan. This a very ambitious and ruthless sheep that once inhabited the now-dying man who had become the ultimate controller of Japan, invisibly controlling all government and private sectors.

Compared with these, After Dark does not seem quite so bizarre at first. It is very late at night, Mari Asai is reading in all-night cafe and some trombone player she had met once at a pool comes and starts talking to her. Quite normal. But in the next chapter we find out that Mari's sister Eri has been asleep for 2 months, only waking every now and then to eat or go to the toilet, and she only does that when the rest of the family is asleep or absent from the house. We are an invisible minute camera that can float in the air in Eri's room, and soon see that she has somehow ended up inside a room on the television in her bedroom, and we realise there is no way for her to get out of that room in the television. There is also a Chinese prostitute who got her period at a delicate moment, and is then assaulted by her client. When the gang that had forced the girl into prostitution learns about this, they feel honour bound to defend her, and begin a hunt for the attacker that will not end until the time, some day, some where, he feels a tap on the shoulder. The gang warns him, 'You'll never get away.'

Amongst all this action are some poignant, disturbing tropes. Mirrors that hold the reflections of a person after the person has left the room. A man with a skin-tight mask that betrays nothing of his features or expressions, and yet we can sense where he is staring. People who can keep such a straight face, and such intense eye contact, that it is impossible to know what they are thinking and only feel intimidated. Television screens, some of which act as mirrors, some providing background noise for characters as they go about their daily routine, one of which turns on all by itself and somehow sucks a person into it. These reflections and masks serve a purpose. They show how disconnected society is now, how impersonal, and somewhat unreadable. They show indifference, in people not caring enough to visibly show any feeling on their faces. There is also a hint of the ever-watchful Big Brother in this, that is to say, beneath any of these masks, reflections, diversions, there could be someone watching you, your movements, even hunting you down.

Yet there's a suprising amount of care in the story as well. Humanity's redeeming quality of helping each other when it is needed, and the forming of deep, intense connections between people. Kaoru lets Mari sleep in an unoccupied room in the love hotel, Takahashi and Mari tell each other about fears and memories they had never told anyone else, and finally, after years of feeling distant and separate from her older sister, though they have both lived at home all the time, Mari discovers that she is very closely bonded to her sister and would not want to be without her.

For all of this detail, and the interweaving of several different narratives, this is one of Murakami's shortest works, at only 200 pages. It is a wonderful introduction to his style, and well worth reading.

Tuesday, March 2, 2010

bite size Capote

A snippet of Breakfast at Tiffany's, purely because it mentions a few Australians. Perhaps this would be more appropriate on ANZAC Day, but I'm posting it now anyway...

On the way home I noticed a cab-driver crowd gathered in front of P. J. Clark's saloon, apparently attracted there by a happy group of whiskey-eyed Australian army officers baritoning 'Waltzing Matilda'. As they sang they took turns spin-dancing a girl over the cobbles under the El; and the girl, Miss Golightly, to be sure, floated round in their arms light as a scarf. p. 19-20, Penguin edition 2008

Image from this listserve post commemorating

WWI on Armistace/Remembrance Day 2008.

It's not quite faithful to the period of the book, since that

is set in the '40s, but Google wasn't being very

helpful today.

Wednesday, February 17, 2010

Reading Kundera - part one

Lately I have been inspired by The Art of the Novel by Milan Kundera. It is a collection of essays, notes and dialogues that covers his ideas about the history, content and purpose of the novel. I have borrowed this copy from a university's library and it smells delightfully of old book though it is not old itself, and, because it is a library copy, I have been copying out whole paragraphs into my journal so that I may revisit them when I have returned the book. If I was not so scrupulously conscientious I might call the library and tell them I 'lost it', but my ideals regarding honesty will not allow such behaviour.

Kundera can be obscure and difficult to understand in some places, as though he expects his audience to authomatically know what he's talking about, but I simply go on reading and aim to get out of it what I can. The Art of the Novel is a book well worth reading more than once for anyone who appreciates novels as more than the notion of 'best seller'. What follows are some of the ideas I have gleaned that particularly struck me as needing to be remembered; this post is by no means a comprehensive review of the book or of Kundera's complete set of ideas, and I don't think any of my posts will ever serve such a function.

I particularly appreciate Kundera's comments on the general public's idea of how the novel should behave, and the writer as well. He denies that novels ought to be realistic, that they must reflect life exactly as it is. 'A character is not a simulation of a living being. Is it an imaginary being. An experimental self... Making a character "alive" means: getting to the bottom of his existential problem. Which in turn means: getting to the bottom of some situations, some motifs, even some words that shape him. Nothing more.' p 34, 35 According to Kundera's ideas, the writer should not be obligated to give an account of the character's entire history of childhood, beliefs, and every thought process, which one finds in so many novels written over the course of the novel's history. Nor should the writer be restricted to simply telling the character's story. Kundera states that he often discusses what the character may be thinking, or what the character might decide to do. This is all in opposition to the traditions of psychological realism, which include the standard that 'The author with his own considerations must disappear so as not to disturb the reader, who wants to give himself over to illusion and take fiction for reality.' p 34 As an aspiring writer who does not want to write according to a set of instructions that say what publishable work needs, I really appreciate what Kundera is explaining, that the art of the novel is malleable and necessary, and that the novelist must aim at something profound: the exploration of existence. It is an understanding that grants the writer the freedom to put in only what is necessary to the story, and not pander to common ideas of what the reader needs to know.

I shall complete this post with a paragraph out of the first essay in The Art of the Novel, 'The Depreciated Legacy of Cervantes', which presents a daunting challenge for the writer who would be true to it: 'The novel has accompanied man uninterruptedly and fiathfully since the beginning of the Modern Era. It was then that the "passion to know," which Husserl considered the essence of Eurpean spirituality, seized the novel and led it to scrutinise man's concrete life and protect it against "the forgetting of being"; to hold "the world of life" under a permanent light. That is the sense in which I understand and share Hermann Broch's insistence in repeating: The sole raison d'être of a novel is to discover what only the novel can discover. A novel that does not discover a hitherto unknown segment of existence is immoral. Knowledge is the novel's only morality.' p 5

Kundera can be obscure and difficult to understand in some places, as though he expects his audience to authomatically know what he's talking about, but I simply go on reading and aim to get out of it what I can. The Art of the Novel is a book well worth reading more than once for anyone who appreciates novels as more than the notion of 'best seller'. What follows are some of the ideas I have gleaned that particularly struck me as needing to be remembered; this post is by no means a comprehensive review of the book or of Kundera's complete set of ideas, and I don't think any of my posts will ever serve such a function.

I particularly appreciate Kundera's comments on the general public's idea of how the novel should behave, and the writer as well. He denies that novels ought to be realistic, that they must reflect life exactly as it is. 'A character is not a simulation of a living being. Is it an imaginary being. An experimental self... Making a character "alive" means: getting to the bottom of his existential problem. Which in turn means: getting to the bottom of some situations, some motifs, even some words that shape him. Nothing more.' p 34, 35 According to Kundera's ideas, the writer should not be obligated to give an account of the character's entire history of childhood, beliefs, and every thought process, which one finds in so many novels written over the course of the novel's history. Nor should the writer be restricted to simply telling the character's story. Kundera states that he often discusses what the character may be thinking, or what the character might decide to do. This is all in opposition to the traditions of psychological realism, which include the standard that 'The author with his own considerations must disappear so as not to disturb the reader, who wants to give himself over to illusion and take fiction for reality.' p 34 As an aspiring writer who does not want to write according to a set of instructions that say what publishable work needs, I really appreciate what Kundera is explaining, that the art of the novel is malleable and necessary, and that the novelist must aim at something profound: the exploration of existence. It is an understanding that grants the writer the freedom to put in only what is necessary to the story, and not pander to common ideas of what the reader needs to know.

I shall complete this post with a paragraph out of the first essay in The Art of the Novel, 'The Depreciated Legacy of Cervantes', which presents a daunting challenge for the writer who would be true to it: 'The novel has accompanied man uninterruptedly and fiathfully since the beginning of the Modern Era. It was then that the "passion to know," which Husserl considered the essence of Eurpean spirituality, seized the novel and led it to scrutinise man's concrete life and protect it against "the forgetting of being"; to hold "the world of life" under a permanent light. That is the sense in which I understand and share Hermann Broch's insistence in repeating: The sole raison d'être of a novel is to discover what only the novel can discover. A novel that does not discover a hitherto unknown segment of existence is immoral. Knowledge is the novel's only morality.' p 5

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)